Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart by Tim Butcher

I picked this book up in a wonderful bookstore in Amsterdam, NL and dived deep into it and since then I have enjoyed the narrative by Tim Butcher. Tim planned to trace back steps of H.M. Stanley in the modern day Democratic Republic of Congo in 2004.

I am very intrigued by the Congo and Africa as a continent in general. I have read several books by Authors (Kapuscinski, Theroux et al) travelling through the various countries and it always seems to be more of an ordeal travel than one of an adventure. I am personally skeptical if I could ever get to visit the Congo ever in my life, but Tim does a great job at narrating his voyage through his book.

He starts his journey just like Stanley did, from Lake Tanganyika in the East and makes his way all the way to the West at Boma, DRC.

Here is a collection of all things Congo that I have stumbled across before, during, and after reading the book.

Paragraphs

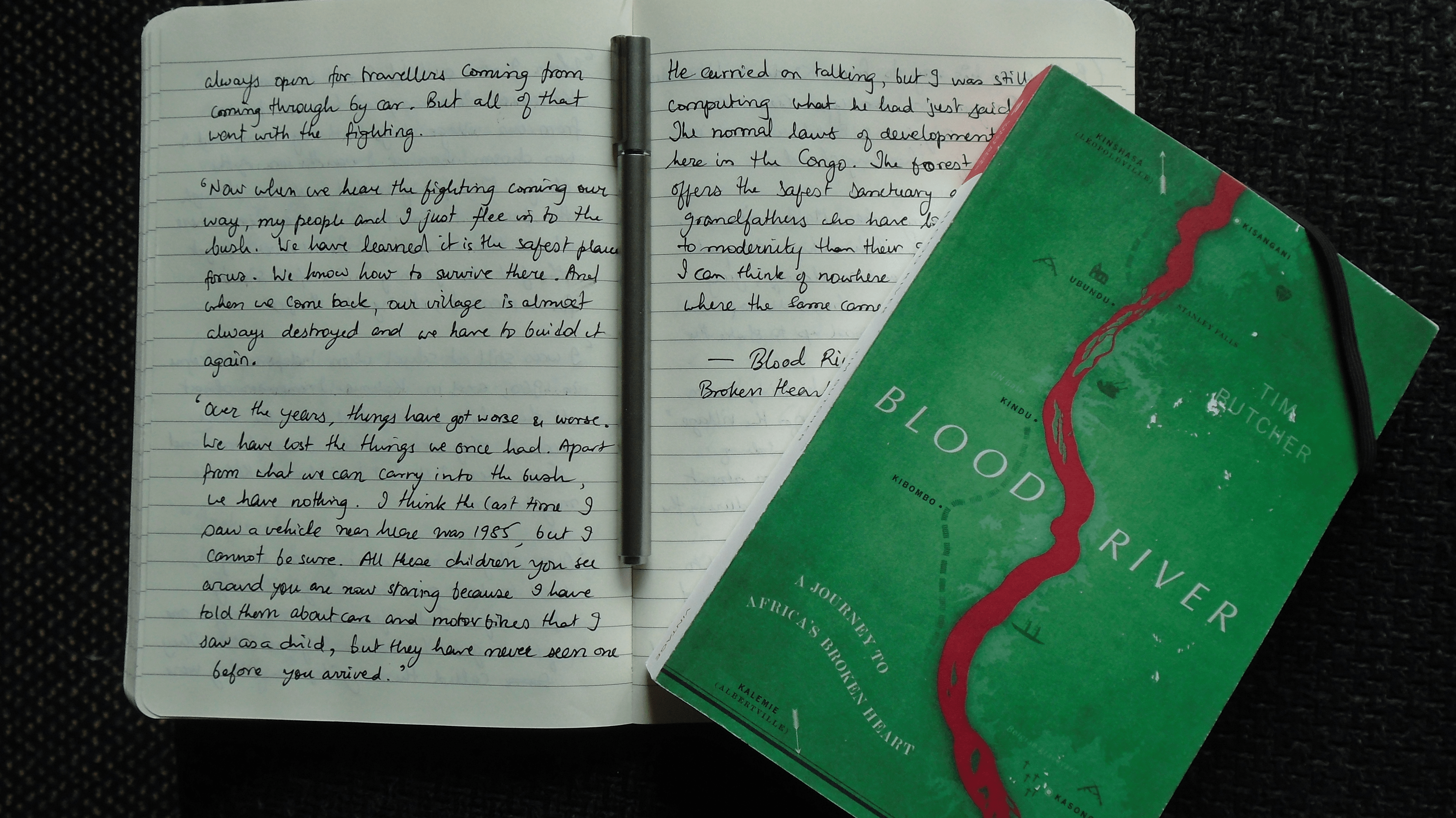

Here are some paragraphs that etched an impression in my mind from the book.

King Leopold’s Fear of Missing Out and Stanley’s Bravado

Context: H.M. Stanley was a reporter for the Telegraph newspaper in the 1800s who is famous for his travel through the Congo River

Stanley’s adventure caught the eye of a minor European Monarch, Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Leopold read about Stanley’s expedition in the newspaper, seeing past the reporter’s colourful account of cannibals, man-eating snakes and river rapids so ferocious they devoured men by the canoe-load. Desperate for a colony that would mark Belgium’s arrival as a world power, Leopold saw rich potential in Stanley’s story. The explorer had found a river that was navigable across much of central Africa and Leopold envisaged it as the main artery of a huge Belgian Colony, shipping European manufactured goods upstream and valuable African raw materials downstream.

Stanley’s Congo expedition fired the starting gun for the Scramble for Africa. Before his trip, white outsiders had spendt hundreds of years nibbling at Africa’s edges, claiming land around the coastline, but rarely claiming land around the coastline, but rarely venturing in land. Disease, hostile tribes and the lack of any clear commercial potential in Africa meant that hundreds of years after white explorers first circumnavigated its coastline, it was still referred to in mysterious terms as the Dark Continent, a source of slaves, ivory and other goods, but not a place white men thought worthy of colonization. It was Leopold’s jostling for the Congo that forced other European powers to stake claims to Africa’s interior, and within two decades the entire continent had effectively been carved up by the white man. The modern history of Africa - decades of colonial exploitation and post-independence chaos - was begun by a Telegraph reporter battling down the Congo River.

Congo’s Slow and Trouble-Ridden Modern Trade

Context: Tim Butcher is on his way from Kalemie to Kasongo. The journey is done on mere 100cc Motorbikes accompanied by two very competent Congolese Odimba, and Benoit. During the arduious journey on non-existent roads, one of the motorbikes breaks down.

As the pair put away their tools I felt a sense of being watched. Turning around, I was shocked to see that we were not alone. A man in rags was watching us, leaning heavily on an old bicycle laden with large plastic containers. He asked if I had any water. I handed over my bottle and he raised his lean face upwards. The sun gleamed on cheeks taut from hunger. He skillfully poured in a mouthful without actually touching the bottle to his lips. He thanked me and prepared to continue on his way, but I asked him where he was heading.

‘I am walking to Kalemie. I am a palm-oil trader. My name is Muke Nguy.'

I was stunned. He still had well over 100 kilometres to walk before reaching Kalemie.

‘I have already walked two hundred kilometers. It has taken me sixteen days.'

I found his words difficult to take in. He was on a 600 kilometre round trip through heavy bush in the equatorial heat, with no food and water. His bicycle was so heavily laden with palm oil that it had long stopped functioning as a means of personal travel. He could not even get to the seat, and, even if he had, I noticed that pedals were missing. His bicycle was a beast of burden, a way to haul goods through the jungle. If the thin, snaking bush tracks were the reins of the Congo’s failed economy, Muke and his heavy burden were just one, solitary blood vessel. He could not afford to bring along food or water when every possible corner of carrying space was used to maximize the load. The only things on the bike I could see that were not tradable on the bike were a battered silver bicycle pump, a roll of woven grass matting and a coil of ivy.

‘I drink when the path crosses streams, and at night I eat what I can find in the bush. I have my mat to sleep on, but sometimes the insects are very strong and they eat me at night. If I get sick I have no medicine.'

He smiled when I asked him what the loop of ivy was for. ‘That is from a rubber tree. If I have a flat, I break the ivy and a glue comes out that will mend the puncture, It is the repair kit of the forest’. For the the first time his gaunt face softened to a smile.

I have always fancied myself as a long-distance athlete. I am large and slow, but at least I have stamina. After the conversation with Muke, I no longer have any illusions about the extent of my stamina. I could not conceive of the strength - physical and mental needed on a forty - or - fifty day round trip through disease-ridden tropical forest. And it was not as if the rewards were huge.

‘I carry eighty, maybe a hundred litres of oil. Maybe I can make ten or fifteen dollars profit when I get to Kalemie. So I spend my money there on things we do not have at home, like salt or lake fish. When I get home, I will see my family for the first time in months and sell some of the salt for another ten or fifteen dollars profit’.

Al`l this effort for $30 and fish supper. I was stunned. Congolese like Muke are out there now, as I write this, sleeping in the bush, swatting insects, kneading blisters on unshod feet, toiling around a Ho Chi Minh trail of survival that shows just how willing many Africans are to work their way out of poverty.

Muke then aked me something.

‘Did you see any soldiers? Any gunmen on the road from Kalemie? Because if they see me they will take what they call “Tax”. Maybe a litre of oil, or maybe what is in my pockets, or maybe even more. Somtimes I can lose all of my profit in a second because in the Congo there is no law’.

Muke was only one of the many bicycle hauliers that I saw. Some carried cannisters of palm oil, a few carried meat - antelope or monkey, sometimes still bloody, but often smoked - and there was even one with thirty or so African grey parrots in home-made cages. The haulier proudly said he was going to make the long and perilous journey from easter Congo all the way to Zanzibar, more than 1000 kms. to the east, where he might get $50 a bird from tourists.

It echoed the slave era, where Stanley saw Arab Slavers in this region driven chain gangs of prisoners for the same long march to Zanzibar to be sold.

The Wheels Spin Backwards in the Congo

Context: Tim, Odimba, and Benoit take refuge in a small village called Mukombo after a long and tedious bike ride and are planning to call it a day. The chief of the village Luamba Mukombo talks to Tim.

I returned to the puddle of firelight and began a piecemeal conversation with the chief. He said he thought he was sixty years old, but he could not be sure. I asked him what he remembered about his country’s history.

‘When I was a child I went to school in Kalemie. It was a great honour for one from our village to go to the big town and I was chosen because I was the son of the chief. My family walked with me through the forest to the place not far from here where the bus passed. I will never forget the first bus journey’. He fell silent for a moment, staring into the fire.

‘I was still at school when independence came in 1960, and in Kalemie I remember almost all the white families fled across the lack because they were scared. I came home and since then I think I have been to Kalemie maybe two times’.

‘Our village here, the one you are sitting in, used to have cars come through it every few days. Just a few kilometres away is one of those guest houses the Belgians built. They called them gîtes and they were always open for travellers coming from and through by car. But all of that went with the fighting’.

‘Now when we hear the fighting coming our way, my people and I just flee into the bush. We have learned it is the safest place for us. We know how to survive there. And when we come back, our village is almost always destroyed and we have build it again’.

‘Over the years, things have got worse and worse. We have lost the things we once had. Apart from what we can carry into the bush, we have nothing. I think the last time I saw a vehicle near here was 1985, but I cannot be sure. All these children you see around you are now staring because I have told them about cars and motorbikes that I saw as a child, but they have never seen one before you arrived’.

He carried on talking, but I was still computing what he had just said. The normal laws of development are inverted here in the Congo. The forest, not the town, offers the safest sanctuary and it is grandfathers who have been more exposed to modernity than their grandchildren. I can think of nowhere else on the planet where the same came true.

Neither Perfect Nor Damn Close

Context: Tim is on his way from Kindu to Ubundu via a Pirogue with a crew of 4 in the Upper Congo river. They rest in a riverine village before heading ahead in teh voyage.

A Pirogue on the Congo River

Image Courtesy: Julien Harneis from Conakry, Guinea / CC BY-SA

The bird flew away when Malike returned. He was not alone. Behind him trouped a group of children and an elderly, grey-haired man wearing a baseball cap. I turned around and stoop up to shake the man’s hand.

‘My name is Liye Oloba’, he said. ‘I am the administrative secretary for the village’. He joined me at my jumble sale of drying clothes and I asked him about the war.

‘When I was young, the ferryboats used to come by here almost every day, up and down, but they never stopped in our village. Our place is tool small. So even though I had not seen a boat for years, I don’t think there is any great difference. The only difference is that gunmen come from time to time and take everything. They came through here a few time in the last few years, but we don’t know where they come from or who they are fighting for. They just take our chickens, and our goats, and our cassava and then leave’.

His baseball cap bore a message in English:

Not Perfect But Damn Close.

It came from the busy trade in donated clothes that has grown up between the developed world and Africa. Clothes given in the west to charity shops are sold for peppercorn sums to traders more interested in quantity than quality. The traders bale them up and ship them here in bulk for sale in street markets. No matter that they are so tatty or unfashionable in western eyes as to have no value, here in Africa people are willing to pay good money for them, and the bizarre clothing I saw all over the Congo suggested it was big business. My favourite was a T-Shirt that had obviously been given to contestants in a 1994 pistol-shooting competition in Dallas, Texas, only to end up, more than a decade later, as the main component of a Congolese villager’s wardrobe. I wondered by what meandering path Liye’s baseball cap ended up on the banks of the Congo River.

The Equator Express

Context: On his way from Ubundu to Kisangani, time rides again with a couple of Congolese on their motorbikes. The path to Kisangani passes through the Equator and the dense Equatorial Rainforest of the Congo, which is the second largest rainforest in the world after the Amazon.

It was during this part of the journey that I had one of the most profound Congolese Experiences. Since we left Ubundu several hours earlier we had seen nothing but forest, track and the occassional pedestrian or thatched hut. The scene I saw in the twenty-first century was no different from that seen by Stanley in the nineteenth century or by pygmy hunter-gatherers over earlier centuries. It was equatorial Africa at its most authentic, seamingly untouched by the outside world.

Suddenly, our convoy stopped. One of the bikes needed refuelling, or one of the riders had taken a tumble, I don’t remember. What I do recall was the sense of Africa at its most brooding. The engines had been switched off and the silence was absolute. There was no birdsong, no screetch of monkeys. Everything edible had long since been shot or trapped for the pot by the local villagers, and the thick canopy way above our heads insulated us from any sounds of wind swishing branches on rustling leaves.

The ground was brown with mud and rotting vegetation. No direct sunlight reached this far down and there was a mushy smell of damp and decomposition. Above me towered plant life filled the void between forest floor and treetop. I feel suffocated, but not so much from the heat as from the choking smothering forest.

I took a few steps and felt my right boot clunk into something unnaturally hard and angular on the floor. I dug my heels into the leaf mulch and felt it again. I slowly cleared away enough soil to get a good look. It was a cast-iron railway sleeper, perfectly preserved and still connected to a piece of track.

It was a moment of horrible revelation. I felt like a Hollywood caveman approaching a spaceship, slowly working out that it proved ife existed elsewhere in time and space. But what made it so horrible was the sense that I discovered evidence of a modern world that had tried - but failed - to estabilish itself in the Congo. It was complete reversal of the normal pattern of human development. A place where a railway track had once carried trainloads of goods and people had been reclaimed by virgin forest, where the noisy buffering of steam engines had long since lost out to the jungle’s looming silence.

It was one of the defining moments of my journey through the Congo. I was travelling through a country with more past than future, a place where hands of the clock spin not forwards but backwards.

The railway track belonged to the Equator Express, a line built by the Belgians to circumvent the Stanley Falls, cutting straight through the Equator. Katharine Hepburn described taking the train to The African Queen set and the grim conditions during the eight hours it took the train to cover just 140 kilometres. Some of the film crew members tried to deal with the heat by pouring baskets of water over themselves, but she judged it was a waste of time because the effort of raising the bucket made you sweat even more, so she sat in a puddle of inertia willing the journey to end.

Nothing like a Primus!

Context: In Kisangani, Tim met with Oggi Saidi, a recommended as a skilled pirogue boatsman, who could take him further down the Congo River. Having gone through some possible options, Oggi and Tim sat down for a couple of beers. Primus Beer was what they drank and is owned by Heineken International.

Back at the hotel, Oggi and I found solace in a bottle of Primus, the local beer. It had been brewed in Kisangani since the colonial era, and across the Congo it enjoys the status of a national instituition. During my research most people with any direct experience of the Congo mentioned Primus. During the various wars and periods of turmoil here, just about the only thing that remained open in the city was the brewery, churning out Primus lager in large, brown litre bottles that bore the name not on a paper label, but on a stencil of white letters glazed direct onto the glass. There were legendary stories about bottles of Primus being opened to reveal human nails inside, or insects, or other detritus too gruesome to go into. But the point was: while every other factory in Kisangani collapsed, the Primus brewery plodded on, filling, recycling and refilling the bottles, time after time, year after year, crisis after crisis.

Each bottle I drank seemed to have its own story. The tiny chinks on the lip or missing letters on the stencil told of boozing sessions and bar fights through the city’s turbulent past. Drinking a bottle of Primus in the sweaty heat of Kisangani made me feel more in touch with the country’s recent history than almost anything else I did in the Congo. And another thing - it tasted great.

Rebuilding with a Chicotte

Context: Tim is still waiting in Kisangani to find a way to head further down towards Kinshasa on the Congo river. He recollects meeting a Greek expat. The expat hat some harsh opinions on what the Congo needed to reestabilish itself.

Whip (chicotte) made from twisted rhinoceros hide

Image Courtesy: Brooklyn Museum / CC Attribution 3.0 Unported

Only a handful of foreigners remain in Kisangani today, from a population that once numbered more than 5,000. During my stay I saw plenty of outsiders, but they were almost all aid workers or UN people, working on short-term contracts, whose experience went back just a few months or years. Many were hard-working, deeply committed to helping the local people, but pretty much all of those I spoke to found the scale of the humanitarian problems simply overwhelming. I heard heartbreaking stories about corrupt Congolese officials pocketing aid money intended for local public-health workers, and local soldiers not just looting aid equipment, but brazenly asking for cash to hand it back to its rightful owners. Many in the aid community spent their time counting the days until their contracts were up and they could go back to the real world.

Yani Giatro’s attitude to Kisangani was very different. He was born in the Congo in 1947, part of a one-huge Greek expat community who had set themselves up as traders, mechanics and farmers during the Belgian colonial period. So large was the Greek community in Kisangani that the city boasted a Hellenic Social Club with restaurant, bar and sports facilities. By the time I got there, the club was barely functioning, but its lunchtime moussaka buffet was one of the few palatable meals available in the entire city.

‘When logic ends, the Congo begins,' Yani said as he bent his face down to spoon up some moussaka. He peered at me over his spectacles as I made my notes.

‘I was born here in the Congo. When my parents took me as a child back to Greece, it was more primitive than here. I used to look forward to coming back to the Congo because it was more advanced than Greece. Can you imagine that?'

‘This city alone use to have a regular flight by a plane spraying for mosquittoes. Every day trucks would drive around the city sprinkling water on the roads to stop the dust rising. You could pick from six cinemas. Eros was my favourite. The whole city centre was electrified. Right at the end of the colonial period, in the 1950s, they put in a hydroelectric power station on the Tshopo (river) with four generators, which was enough for the whole city’.

‘But even if you accept the fighting, the wars and the struggle for control, what do you have today? Nobody with any interest in making this place work, apart from a few aid workers’.

Yani raised his eyes and a club waiter came running with a bottle of Primus. He lit a cigarette and drew heavily on it before leaning forward conspiratorially.

‘You see him?' he asked quitely, flicking his eyes in the direction of a photograph of the country’s president, Joseph Kabila, catapulted into the job in his twenties after his father, Laurent Kabila, was assassinated.

‘What skills does he have to run a country like this, or even a place like Kisangani? In all his life he has never been here, and this is the second city of the country he is president of. It is ridiculous. Christ, before his father took over this country, the young Kabila was driving taxis for tourists in Tanzania, and now he is meant to be a national leader!' His harrumph of scorn was so loud it made the waiter jump.

‘Who is there who actually wants this place to work? I don’t see anybody. Let me give you an example. An aid group went to the Tshopo power station in the last couple of years. They found three of the four generators were broken, So they raised the money and shipped replacements to Matadi, the country’s main port down near where the Congo River reaches the Atlantic. And they flew in engineers to Kisangani ready to fit everything’.

‘So what happenend? The customs, the officials, the people down at Matadi blocked the generators from coming in. The foreign engineers got more and more frustrated until they eventually left, God knows where the new generators ended up, and the lights still go out here in Kisangani’.

He leaned forward again, fixed my gaze and whispered. ‘The Congo was built with the chicotte, and the only way to rebuild it will be with the chicotte.' He was referring to a whip made from dried hippopotamus hide, which the early Belgian colonialists used savagely when dealing with their subjects in the Congo. Even today, almost fifty years after the Belgians left, the chicotte endures as a sinister symbol of their brutality.

Posts and Articles

A collection of things I knew of the Congo prior to reading the book.

Anthony Bourdain’s Congo

If you can, watch Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown episode on the Congo.

- Bourdain’s Field Notes on Congo

- Things to know before go to Eastern Congo

- Bourdain’s interractions

- Eat like Bourdain: Congo

Documentaries

The Congo Dandies

My initial introduction to Congo was made through one very peculiar documentary by Russia Today’s (RT) Documemtary channel on YouTube. It is about the Congo Dandies or La Sape. It illustrates a complete paradox between overtly well dressed individuals in the big cities of Kinshasa and Brazzaville amidst abject poverty and how it is a elite culture even though the Dandies themselves are subjected to poverty.

Vice Guide to Congo

Suroosh Alvi and Vice explore the notorious Coltan mines of Eastern Congo, a conflict mineral used in nearly every electronic device on Earth.

Vice Fringes: Joseph Kony and M23

Another fantastic documentary on the refugees and the rebel factions of the DRC.

BBC Africa: Congo

A very recent documentary on the Congo by BBC, where the team traverse through the DRC.

Congo, My Precious

An extremely heart-shattering documentary on the Coltan Mines in the DRC through the soul of a Congolese.